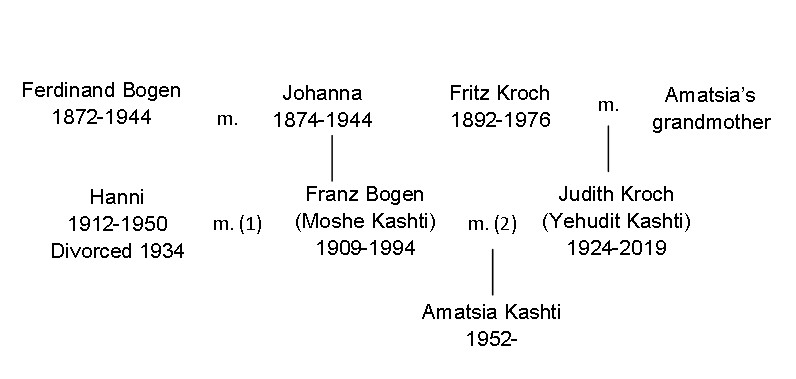

Amatsia’s paternal grandfather Ferdinand Bogen (1872-1944) was a travelling salesman in Berlin. On the outbreak of World War One, Ferdinand felt that he had to do his duty to the Kaiser and so volunteered to serve in the German army. The old (aged 42) Jew was promptly kicked out of the recruitment office, but this did not deter him from buying a mule and cart, with which he organised a postal service for Jewish families whose sons served on the Eastern front. For the next four years he was absent from his family, and they suffered poverty and hunger. As a reward for his efforts, Germany killed him 25 years later.

Amatsia’s paternal grandparents, Ferdinand and Johanna (1874-1944), and his father’s sister Marianne (1911-2010) stayed in Germany after World War One. His aunt, however, managed in 1939 to get a visa to be a nanny in Britain as she was a qualified Montessori kindergarten nurse. She became a teacher and died in London in 2010 aged nearly a hundred. When World War Two broke out, Amatsia’s grandparents escaped to Holland and stayed with members of their family. They lived there in semi-hiding until 1944 when, in their seventies and in poor health, they were put together with 50 other Jews in a cattle wagon on a train going to Auschwitz. There is no record of their arrival there and it is likely that they did not survive the journey, which could have lasted up to two weeks.

When their son, Franz (1909-1994), Amatsia’s father, finished his law studies in 1932, the Nazis were already in power and anti-Semitic legislation restricted how he practised his profession. He recounted that, when he was sitting one day in court as a junior judge, with cape and all, the senior judge turned to him and said: ‘Dear colleague, today I saw them hitting Jews at the entrance to the building and I would advise you to leave through the back door’. From that moment on he couldn’t stay to listen to the proceedings and made two decisions. First, he was going to leave from the back door and second, he was going to emigrate to Palestine as soon as possible.

Palestine had been a British territory mandated by the League of Nations since 1929, following the first Arab uprising known by the Jews as ‘The Riots’. To emigrate there people were required to produce a certificate proving that they had a profession that was needed in the colony – and a judge in Germany was not one of those professions. So Franz took a two-year apprenticeship in plumbing and obtained his diploma, which enabled him to obtain an immigration certificate. As the certificate he obtained was for a couple, he married a fellow Jew who also wanted to emigrate in Berlin Town Hall so that she could go too. When they arrived in Palestine in 1934 they went to Jaffa Town Hall and got a divorce.

On arrival in Palestine, Franz was one of the founders of a kibbutz in Jezreel Valley (now in northern Israel). However, he soon discovered that he was not destined to be a plumber and so he became an administrator in the kibbutz. His first genuine wife, Hanni (1912-1950), had trained as a nurse in a TB hospital in Holland in order to qualify for entry to Palestine, but while at the hospital she too contracted TB. Before dying she was in a sanatorium in Switzerland. To be able to visit her, Amatsia’s father got work in the Israeli Foreign Office and was sent to Holland. He visited her in Switzerland each month until her death in 1950.

When changing trains in Paris on the way to Switzerland one time Franz stopped off to visit a family living in Paris who had left Switzerland after the war. Here he met the woman who was to become his second wife and Amatsia’s mother. Amatsia was born in Paris in 1952, but within a year the family went to Israel to live.

Amatsia’s mother Judith (1924-2019) came from a wealthy family in Leipzig who owned a bank and had a property empire. With the rise of the Nazis to power, and even after Kristallnacht (Night of the Broken Glass) in 1938, the family believed that their fortune would shield them from any harm and that the nightmare regime would soon be over. However, when the war broke out they were all incarcerated and only released on condition that they signed over their wealth to the German Reich. They did so and decided to escape individually and then meet up in Paris. The family dispersed to Holland, Belgium, France, Switzerland and Italy, and reunited eventually as planned, on the outskirts of Paris.

In France they thought they would be protected but it was not to be. When the Germans invaded France the family escaped by foot and by horse and cart towards a village in the Free France zone controlled by the Vichy Government. Twenty-five years earlier, Amatsia’s maternal grandfather, Fritz Kroch (1892-1976), had become a friend of a French Jew, Felix Goldschmidt (1898-1966). When he saw that France was at risk, Felix bought a small cottage on the outskirts of a small village deep in central France called Mézières-en-Brenne as a possible refuge. There Amatsia’s grandparents with his great-grandmother and four children met Felix, his wife and four children and here both families (13 people) stayed for a year and a half.

The entire village knew of the Jewish family and kept it secret. The mayor even managed to save food vouchers to feed them. One night a village policeman cycled over and told them to get ready quickly and escape because at dawn a German truck would be rounding them up and deporting them. That night the family ran to a faraway vineyard of a local friendly farmer and hid in a hut for two weeks before fleeing east to Switzerland. By various means, and with many complications, they made their way there and were put in a refugee camp. At one point on their escape route the notorious Klaus Barbie, who was chief of Gestapo Department IV in Lyon, put some of them in prison. His nickname was the butcher of Lyon. Fortunately, all the family managed to get away.

Once Amatsia’s family was in Israel, Franz Bogen became Moshe Kashti (the translation of Bow from German to Hebrew) and worked for the Defence Ministry for the rest of his career until his retirement. Judith (pronounced Yehudit in Hebrew) worked as a medical secretary in a large hospital. When she retired, she bought a computer and wrote down the story of her escape from Germany. She wrote it in German and it was translated to English (‘Running for Survival’), Hebrew and French.

After Amatsia’s father died, the family added the names of his parents to his memorial gravestone, as they were never buried.

To celebrate his 60th birthday Amatsia decided to retrace the route his mother had taken to Switzerland by walking the route. His son accompanied him for part of the way. His mother was still alive and was able to keep in contact with him by email and reminisce about places Amatsia was calling at on his journey – making it a reflective time for Amatsia.

In 2017 Amatsia and his cousins contributed to the construction of a monument, ‘The Fountain of Liberty’, in Mézières-en-Brenne’s market square to commemorate the village’s help in saving his mother’s family, and in particular for Thérèse and Henri Morissé, the farmer and his wife who hid the family in their vineyard. They arranged for the Morissé descendants to receive the medal of Righteous Among Nations from the Yad-Vashem Holocaust museum in Jerusalem, a medal awarded to non-Jews who risked their lives saving Jews. This was done in a formal ceremony attended by French and Israeli officials as well as representatives from Yad Vashem (The World Holocaust Remembrance Center) and 14 members of the family.

De Leipzig a Mézières-en-Brenne: Histoire d’un episode de la vie de deux familles et de leur rencontre improbable [From Leipzig to Mézières-en-Brenne: the story of an episode in the life of two families and their unlikely encounter]

Photo taken from a YouTube video of part of display at the fountain’s inauguration in 2017

Interviewed by Tony Rogerson on 11 April 2013