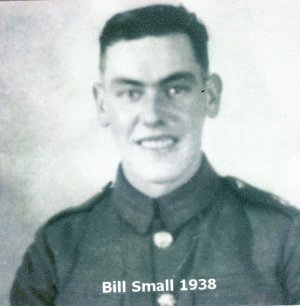

Albert William (Bill) Small was born on 28 June 1919 at South Stoke in what was then Berkshire. He married May Phyllis Elizabeth Dandridge in the same village on 5 April 1947. She was born on 11 May 1926 and died in 1997. In 1960 Bill and his wife were living at 3 West Lockinge Farm, near Wantage (also then in Berkshire). Following his first wife’s death, Bill married Stella Blanche Dorman in 1997 in Abingdon district. Stella, who was born on 10 August 1921, died in 2006 and Bill died in 2007. They had supported each other when their former spouses had been ill and, following their marriage, lived together at Bigwood, one of the mobile home parks in Radley.

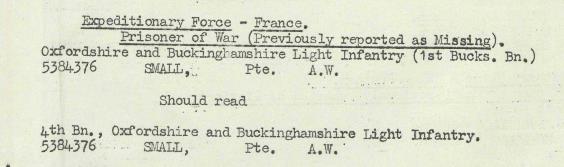

Bill joined the 4th Battalion of the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry (4th Battalion Ox and Bucks) as a private and his army number was 5384376. When he was taken prisoner of war, his POW number was 14836. On the POW lists for 1943-1945 he was listed as being in Camp 344.

Bill was a very popular member of the Radley Retirement Group. He was their first aid officer and enjoyed going on group holidays. Anyone who went on one of these holidays with him will remember the hilarious costumes he dressed up in for a fancy dress evening. He was asked to talk to the Group about his experiences during the war. Below is his account.

“At home in the 1930s life was hard. I went to work on Saturdays, aged nine, from 8am to 3pm earning 8d – giving 6d to my mother and keeping 2d for myself.

After leaving school aged nineteen, I wanted to do something different with my life so I joined the Territorial Army, the 4th Battalion Oxon and Bucks Light Infantry – and from there my journey began.

We went to the camp at Lavant near Chichester for 14 days’ training. What a wet time it was! We had to sleep in tents, ten men in each, lying on grass. After basic training, I returned to farm work for a while until, in September ’39, a call came over the radio to report to Goring-on-Thames. We had to sleep in the village hall on very hard floorboards. A week later we were formed up to make a battalion of 48 divisions including Berkshire and Gloucestershire regiments and went to Woolton, near Newbury. Training went on all the time – I was a sniper then – but men from the 14-18 was said to get out of that so I became a stretcher bearer (first aid). We did a lot of manoeuvres on Snelsmore Common, near Newbury.

We left Newbury in January 1940 from East Woodhay station on a steam train to catch a boat from Southampton to Le Havre, France. On the Channel crossing we were chased by enemy submarines, which made it a four and a half hour crossing! A very cold and rough crossing too!

We landed at Le Havre early in the morning with the ground covered in snow and ice. We marched for about ten miles to temporary billets. We then went by steam train to Attichy for a short stay before continuing by train at the end of January to Roost-Warendin near Douai. We had to share baths, 12 men one after the other in a metal footbath. We had to undress and with a towel around us run across the snow to the bath, about 20 yards away surrounded by hessian. Very cold! After a few weeks we went to Arras for a weekly bath at the miners’ pits – much better.

Early 1940 was spent training for trench warfare and building the Gort Line, which was a continuation of the Maginot line, from Luxemburg to the north coast of France. This was a line of anti-tank trenches and pill boxes 200 yards between.

Germany invaded on 10 May 1940 through Luxembourg, a neutral country, running around the back of the Maginot and Gort lines of defence, overrunning all in their paths – blitzkrieg as they called it. We were at Waterloo in Belgium, and after a day’s fighting and many strafing sorties, we had to pull back to the Charleroi Canal. After another stand then we moved to Ath in Belgium. As we retreated through the town, four abreast in lorries, we were bombed and strafed by many Stukas. I was in the third lorry from the level crossing when a lorry carrying ammunition was hit and went up in the air about six feet. I jumped out of the left hand side of the lorry and it was strafed on the right. One chap I spoke to was wounded – his war was over; seven men were killed on his side of the lorry.

We moved onto the Albert Canal to form a new line of defence. The canal was red with blood from the Germans trying to cross over. They gave up after half a day.

We went on to form a line of defence at Enghein on 17/18 May, then marched at night for 26 miles to a wood by the River Escaut on 19 May.

At one stage I had to go to the town to fetch bread for everyone after being given the password for the day. Near to the town the bridge was being guarded by our boys and a sentry jumped out with a bayonet at my throat. Halt – password? I had forgotten it. I froze. About eight men were around me with fixed bayonets and I had to be taken to an officer to be OK’d. I heard them click the bolt on their gun and I swore at them not to shoot! A very close shave. I was able eventually to go and fetch bread for the troops.

Another time a shell landed outside our café HQ wounding the guard and bending the runners off the shutters well out of shape. The chap sitting opposite me had the belt taken off his back – another close shave.

We retreated to Bois and got heavily shelled day and night for 36 hours continuously. We were going to blow up the bridge in Bois and I remember thinking I had time to go to the toilet first – a board with a hole in the top – but when the bridge went up so did I, through space!

As I have already mentioned the Charleroi Canal was our line of defence and I had to go to HQ with a message. Someone had to take the ammunition to the front line so I was asked to go. We had a Bren gun carrier (small tank) and put boxes of ammo on top of the tank and off we went about 300 yards across open ground to the front line with bullets flying everywhere. When we got to the front line I had to crawl along the top to push the boxes of ammo off into the trenches where our boys were dug in. Coming back was worse but I am still here.

We moved to Cassel on the hill, being continuously bombed and strafed day and night for four days. Cut off from the main army we had to fight our war listening to BBC Radio, which was four days behind the real news. At Cassel I had to go down into ‘no man’s land’ between us and the German line to collect the wounded. We were fired on as we crawled down and back with bullets moving the soil around our tin helmets.

One time on arriving at the Regiment Aid Post (hospital), a shell landed outside in the square as we were entering the doorway. It blew us down the corridor to the operating table. On returning to Cassel recently I saw the building. It’s now a doctor’s surgery but still has the shrapnel marks around the door. We also sheltered in a cellar of a house, which took a direct hit. We had to force open the cellar door to get out finding the rest of the house was gone.

At 10 o’clock one night we had orders to fight our way out of Cassel and make for Dunkirk. On the way down at a place called Watou, German tanks came over the brow of the hill. We dived into a ditch and the tanks went right over the top of us. No-one was hurt. A little while later we had to make a stand at Wormhout, 12 miles south-east of Dunkirk.

Throughout the Second World War there was no shortage of senseless killings, but little did we realise we would encounter the SS Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler, some of Hitler’s favourite troops.

The British troops put up a brave resistance against heavy odds. We claimed batches of their casualties including their commanding officer Schutzuk. Many SS troops were stoked up after the fierce battle but, when word got out that their commanding officer had been wounded, things got out of hand.

Some of our soldiers who had been wounded were shot dead. About 20 of our men had been lined up and shot. A hundred were double marched over fields to a barn; those who fell were beaten or bayoneted. The SS troops then threw hand grenades into the barn. Twenty survived as they were under the dead. The troops rounded up what was left, about 30 men, myself included. We were lined up in the field with a machine gun put in front of us. Many things went through my mind about how to dive left or right or fake death but, at what seemed like the last moment, a German officer came down the road shouting. The machine gun was removed and the German army took over. I then had to help pick up the wounded and rejoin the main German column for marching to a POW camp.

Our last week of fighting we had had very little food and, after being taken prisoner, we had to march 15-20 miles a day in the heat for three weeks to Germany scrounging what we could to survive.

On arriving in Germany they asked for people who did farm work and could ride a horse, so I volunteered to go. So they took us back to the French coast to pick up three horses each to ride back into Germany. On the way back a lot of chaps who could not ride well lost their horses, so I had to round them up and return them as we went along. Sometimes it meant riding about half a mile from the column but it was impossible to escape. There were Germans everywhere. After about ten days riding we arrived back in Germany with bow legs and a B…. sore behind. Then on to Stalag VIII-B Lamsdorf.

Our camp was at Lamsdorf. We had two small rotten potatoes and a slice of bread each day, nothing else. Christmas 1940 we left peelings on the cookhouse floor and we were told it was ‘too much waste’. We were given prunes and had potato peelings with prunes.

This carried on for a long time until Red Cross parcels began to arrive – our lifesaver. One parcel was shared between ten men. This consisted of a small bar of chocolate, quarter of a pound of tea, a small packet of plain biscuits, a small tin of ham, raisins and a few other items. After two years things got better still – one parcel per man per week. The raisins in the parcels were soaked to make wine at Christmas. This went on until ‘jerry’ found it and confiscated it for themselves. We had to hide our mixture but we had other cans for them, which we pee’d into – it looked the same. They never took it again.

We had to shower and delouse every six weeks and our clothes were taken away to be steamed. They came back with metal tags on them, which burned your body when they were thrown at you. It was cold but you did the best you could. I had Stalag number like everyone else. 14836 was mine. This was hung around your neck, your head was shaved and a photograph taken. Of course our war did not end there. We could be bombed by the RAF at night and the Yanks in the day.

The French POWs joined us at Poznań. One French officer wished to learn English so I got him to say “I am a B….. fool” so every time he went up to anyone he would salute and say “I am a B…… fool”. Everybody laughed and told him “very good, very good”. All went well until an English-speaking Frenchman arrived and told him what he was saying. That was the end – he would not speak to me again.

I moved around several camps – XXI-A, XX-B, Poznań [Stalag XXI-D], etc. My last camp was Stalag VIII-B Lamsdorf. It was five years after capture when the war went the other way.

One night the Russian army overran our camp and the Germans fled, but in the morning when the Russians withdrew and our guards came back we had just an hour to leave. We left in batches of a hundred men and had to march through the Erzgebirge mountains. We had to dig into the snow for warmth at night, minus 40 degrees with wolves for company. We eventually reached Prague in Czechoslovakia and then made for Nuremburg in Bavaria. We were shelled as we were entering British-held territory. A lone British tank arrived – at last we were free. We were told to make our way down to where the Yanks were about three miles away. Some of our chaps were killed after five years as a POW as the Yanks didn’t recognise them.

From Nuremburg we were taken about 50 at a time in lorries to catch a Dakota at Augsberg to Lyon in France. Then we were put into a Lancaster bomber in the empty bomb bays with no time to think about what was going on. Next stop an aerodrome in southern England. We stayed overnight then had passes to Paddington, then Goring. Home at last! Two days from being freed to being at home.

After six weeks’ leave I had to report back to Aylesbury for a few weeks, then down to Fleet near Aldershot. I was transferred to Royal Army Medical Corps, then to Checkendon near Wallingford to look after a camp of Polish soldiers as a medical orderly.

I then went to the Churchill Hospital, Oxford, to take over from the Americans. It was one of their hospitals and had been built named after Sir Winston.

Then it was ‘demob’ time and I went to Taunton in Somerset. I had nightmares for about six months over all that had happened during the previous five months. I still have the odd one even now, 56 years later. After being demobbed I was given a job at the Royal Berkshire Hospital in Reading as a medical orderly. I had a job to get there, so being one minute late they stopped me an hour’s pay. I finished right away. I went back to farm work because by then I had met a girl who lived on the farm, who I later married. Later on I joined the St John’s Ambulance, having an ambulance parked outside on 24-hour call. It also had to treat minor injuries, cuts, etc. I passed more certificates in home nursing so I had a badge on the door in the village of West Lockinge, doing nursing at night to relieve the doctor’s surgery.”

Notes on the above account

The German army had launched its invasion of the Low Countries on 10 May 1940, ending what had been called the phoney war. The British Expeditionary Force had been sent over in readiness and had spent time building pillboxes and other defences. Unfortunately, the Germans invaded through the poorly defended Ardennes Forest, having defeated the Dutch and invaded Belgium. The 4th Battalion of the Oxon and Bucks Light Infantry tried to defend the River Scheldt, but were pushed back into France and found themselves in the Dunkirk area. The evacuation of British troops from Dunkirk started on 26 May. The 4th Ox and Bucks took part in the defence of Cassel until 29 May but were eventually encircled by German Forces near Watou and forced to surrender. Most of the soldiers were held as prisoners of war for the next five years.

Based on the transcript of a talk given by Bill to Radley Retirement Group in November 2002